When Curiosity Gaps Backfire: Effects of Headline Concreteness on Information Selection Decisions

- Marianne Aubin Le Quéré, Cornell University

- J. Nathan Matias, Cornell University

How much information should a headline reveal? Our research suggests that there is a sweet spot: headlines that are too concrete or too vague lead to fewer clicks. Using nearly 9,000 experiments, we show how headline wording shapes online attention and economics. This research marks the first time this “curiosity gap” is empirically demonstrated to be effective using data from a field experiment.

“The curiosity gap: too vague, and I don’t care, but too specific, and I don’t need to click the link.” – Peter Koechley, co-founder of Upworthy

Citation and Resources:

- Aubin Le Quéré, M., and Matias, J.N. (2024) When Curiosity Gaps Backfire: Effects of Headline Concreteness on Information Selection Decisions. Nature Scientific Reports.

- Use the concreteness metric in your own work

- Original Dataset

- Preregistration

The curiosity gap, in action

Scientists have described that information gaps may arise when people are exposed to medium amounts of information. Think of your desire to know the answer to a trivia question: if you’re confident you know the answer, or you have no idea what the answer is, you won’t be curious to know the real answer. However, if you think you know what the answer is, you will get that tip-of-the-tongue feeling that makes you need to find out more.

Headline writers have been using this technique for years, stylized as “the curiosity gap.” A classic example is the video Zach Wahls Speaks About Family, which became viral only after being given the headline: Two Lesbians Raised A Baby And This Is What They Got. This headline seems designed to pique reader curiosity by obscuring crucial information.

But scholars don’t agree about whether curiosity gaps actually work in real life. Previous lab experiments and large-scale data analyses have found conflicting evidence. We argue that our metric — which is continuous, not binary — allows us to resolve these accounts.

So, do these curiosity techniques actually work for attracting more clicks? Should headline writers be using them if their goal is to maximize engagement?

What we found

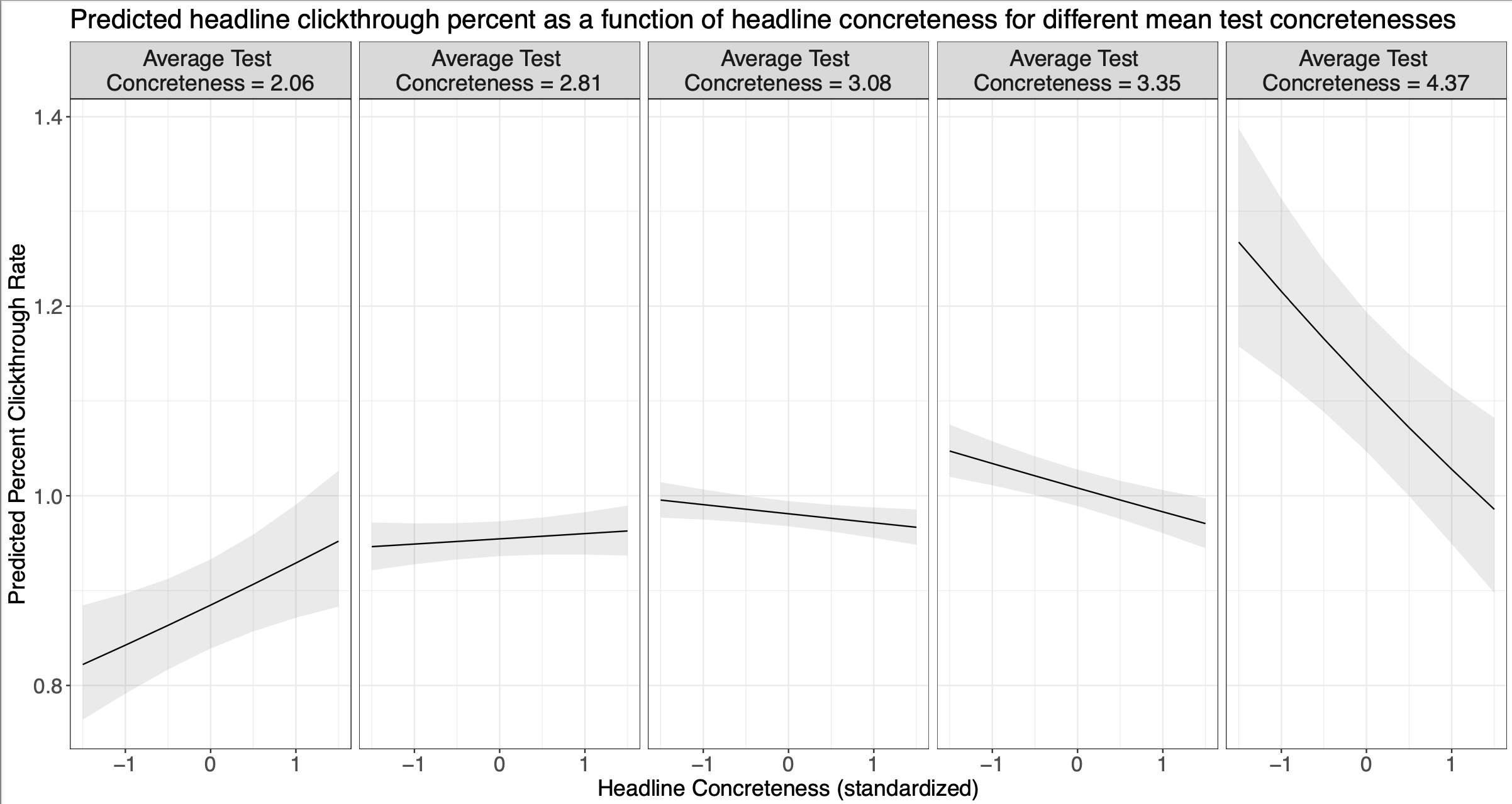

Our research shows that the most effective headlines strike a balance between being vague and detailed. For each headline in our dataset, we modeled the amount of concrete bits of information in the sentence. When all headlines in an experiment are vague, the most concrete headline attracts more clicks. Conversely, when all headlines in an experiment are very detailed, the vaguer headline attracts more clicks. Together, these findings suggest that the most effective headlines convey some amount of information – but not too much.

In our dataset, we find an asymmetric relationship. These findings are based on a dataset from the publisher Upworthy, who are known for this kind of curiosity gap headline. Our model predicts that only 8.7% of headlines published by Upworthy would benefit from being more concrete, versus predicting that for 50.9% of headlines, increasing concreteness would significantly decrease clickthrough rates. However, Upworthy’s audience is likely to have a penchant for clickbait-style headlines, so we can’t assume this asymmetry will exist for all publishers.

How we did it

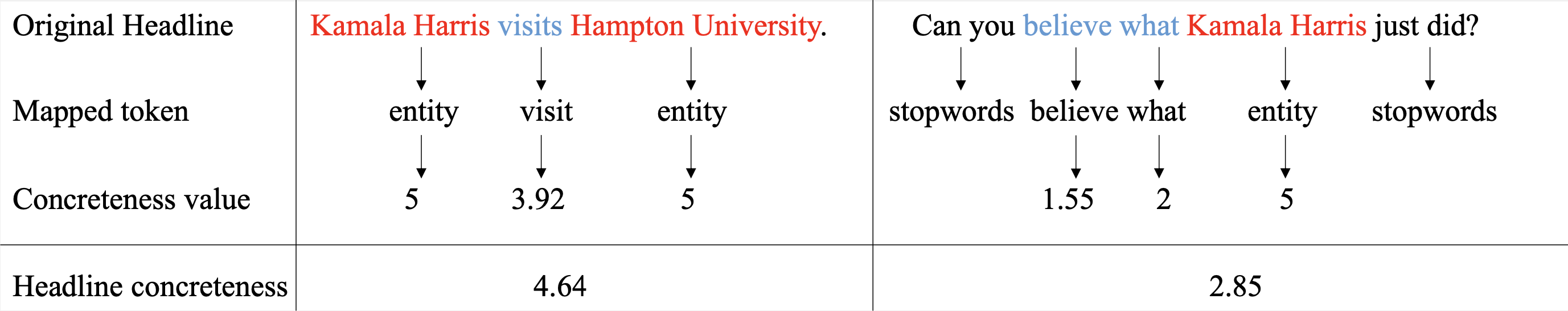

The most novel part of our analysis is a new metric we call sentence concreteness. This metric is based on a dictionary developed by other scholars that maps individual words to a human-assigned concreteness score. For our measure, we simply take the average of all concreteness words in a sentence. We additionally assume that entities, such as celebrity names or specific places, should be counted as highly concrete. This metric was validated by human crowdworkers. The following figure shows this process in detail:

Once we know how concrete each headline is, we run our main analysis. Since headlines were tested against each other, we can use this data to predict which headline will perform better, based on its concreteness. We model this effect of headline concreteness at different levels of average concreteness, and show conclusively that the effect goes from significantly positive to significantly negative.

For a more detailed explanation, refer to the paper.

Can I use the concreteness metric in my work?

Yes! We have made a public python library available for use by researchers and news organizations. You can import this metric using pip and label any sentence with a continuous scale of concreteness. If you do use this metric, please cite our work:

Aubin Le Quéré, M., and Matias, J.N. (2024) When Curiosity Gaps Backfire: Effects of Headline Concreteness on Information Selection Decisions. Nature Scientific Reports.

Acknowledgements

Marianne and Nathan are incredibly grateful to those who have helped this project come to fruition.

- Mor Naaman

- Kevin Munger

- David Karpf

- Good/Upworthy

- David Mimno